I have been taking a break from photography this last year. That’s because I didn’t feel I had anything to say certainly not about Calderdale. I said that I didn’t want to see mud and tree mould in the winter any more. I know Calderdale is a really beautiful place to live. Yet I’m finding inspiration elsewhere.

I began this work a year ago. It features quotes from various authors taken out of context and made to serve changes to the climate. We have had about three months fine weather with very little rain. It’s very unusual for Yorkshire and the moors have been burning. We live a life of weather extremes.

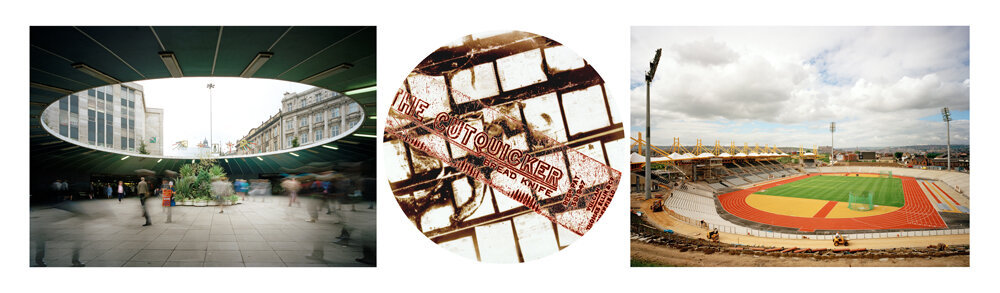

I wanted the citations in the images to be hand drawn, one of the reasons being to take on a personal look. They are also truncated because it reflects that anything we do is snatched. I took the photographs on a visit to Portugal.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the… Charles Dickens

I’d like to extend the series, but as I have found, the background image is important. It can’t just be any old random image. There is also a problem of quotations as I find it difficult to find the most appropriate. The first is the famous Dickens quote from A Tale of Two Cities, the second is Jean Rhys by way of Per Petterson in Out Stealing Horses.

…the difference in the way I was frightened and the way I was happy. Jean Rhys reused by Per Petterson